Translation of the Gospel According to John

At that time Jesus said to the Pharisees: I am the good Shepherd. The good Shepherd giveth his life for his sheep. But the hireling, and he that is not the shepherd, whose own the sheep are not, seeth the wolf coming and leaveth the sheep and flieth: and the wolf catcheth and scattereth the sheep: and the hireling flieth, because he is a hireling, and he hath no care for the sheep. I am the good Shepherd: and I know Mine, and Mine know Me, as the Father knoweth Me, and I know the Father: and I lay down My life for My sheep. And other sheep I have that are not of this fold: them also I must bring, and they shall hear My voice, and there shall be one fold and one shepherd.

A Message From Pope Benedict XVI’s Homily for Mass of Ordination to the Priesthood, May 2006.

The Gospel we have heard this Sunday is only a part of Jesus’ great discourse on shepherds. In this passage, the Lord tells us three things about the true shepherd: he gives his own life for his sheep; he knows them and they know him; he is at the service of unity.

…

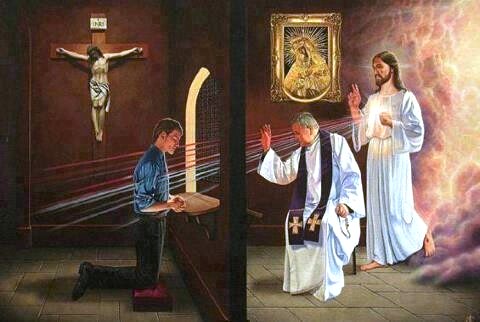

The first one, which very forcefully pervades the whole discourse on shepherds, says: the shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. The mystery of the Cross is at the centre of Jesus’ service as a shepherd: it is the great service that he renders to all of us.

He gives himself and not only in a distant past. In the Holy Eucharist he does so every day, he gives himself through [the priest’s] hands, he gives himself to us. For this good reason the Holy Eucharist, in which the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross remains continually present, truly present among us, is rightly at the centre of priestly life.

And with this as our starting point, we also learn what celebrating the Eucharist properly means: it is an encounter with the Lord, who strips himself of his divine glory for our sake, allows himself be humiliated to the point of death on the Cross and thus gives himself to each one of us.

The daily Eucharist is very important for the priest. In it he exposes himself ever anew to this mystery; ever anew he puts himself in God’s hands, experiencing at the same time the joy of knowing that He is present, receives me, ever anew raises and supports me, gives me his hand, himself. The Eucharist must become for us a school of life in which we [priests] learn to give our lives.

…

Secondly, the Lord tells us: I know my own [sheep] and my own [sheep] know me, as the Father knows me and I know the Father (Jn 10:14-15).

Here, two apparently quite different relationships are interwoven in this phrase: the relationship between Jesus and the Father and the relationship between Jesus and the people entrusted to him. Yet both these relationships go together, for in the end people belong to the Father and are in search of the Creator, of God.

When they realize that someone is speaking only in his own name and drawing from himself alone, they guess that he is too small and cannot be what they are seeking; but wherever another’s voice re-echoes in a person, the voice of the Creator, of the Father, the door opens to the relationship for which the person is longing.

When they realize that someone is speaking only in his own name and drawing from himself alone, they guess that he is too small and cannot be what they are seeking; but wherever another’s voice re-echoes in a person, the voice of the Creator, of the Father, the door opens to the relationship for which the person is longing.

Consequently, this is how it must be in [the priest’s] case. First of all, in our hearts we must live the relationship with Christ and, through him, with the Father; only then can we truly understand people, only in the light of God can the depths of man be understood. Then those who are listening to us [priests] realize that we are not speaking of ourselves or of some thing, but of the true Shepherd.

…

Lastly, the Lord speaks to us of the service of unity that is entrusted to the shepherd: I have other sheep that are not of this fold; I must bring them also, and they will heed my voice. So there will be one flock, one shepherd (Jn 10:16).

John repeated the same thing after the Sanhedrin had decided to kill Jesus, when Caiaphas said that it would be better for the people that one man die for them rather than the entire nation perish. John recognized these words of Caiaphas as prophetic, adding: Jesus should die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad (Jn 11:52).

The relationship between the Cross and unity is revealed: the Cross is the price of unity. Above all, however, it is the universal horizon of Jesus’ action that emerges.

If, in his prophecy about the shepherd, Ezekiel was aiming to restore unity among the dispersed tribes of Israel (cf. Ez 34:22-24), here it is a question not only of the unification of a dispersed Israel but of the unification of all the children of God, of humanity – of the Church of Jews and of pagans.

Jesus’ mission concerns all humanity. Therefore, the Church is given responsibility for all humanity, so that it may recognize God, the God who for all of us was made man in Jesus Christ, suffered, died and was raised.

The Church must never be satisfied with the ranks of those whom she has reached at a certain point or say that others are fine as they are: Muslims, Hindus and so forth. The Church can never retreat comfortably to within the limits of her own environment. She is charged with universal solicitude; she must be concerned with and for one and all.