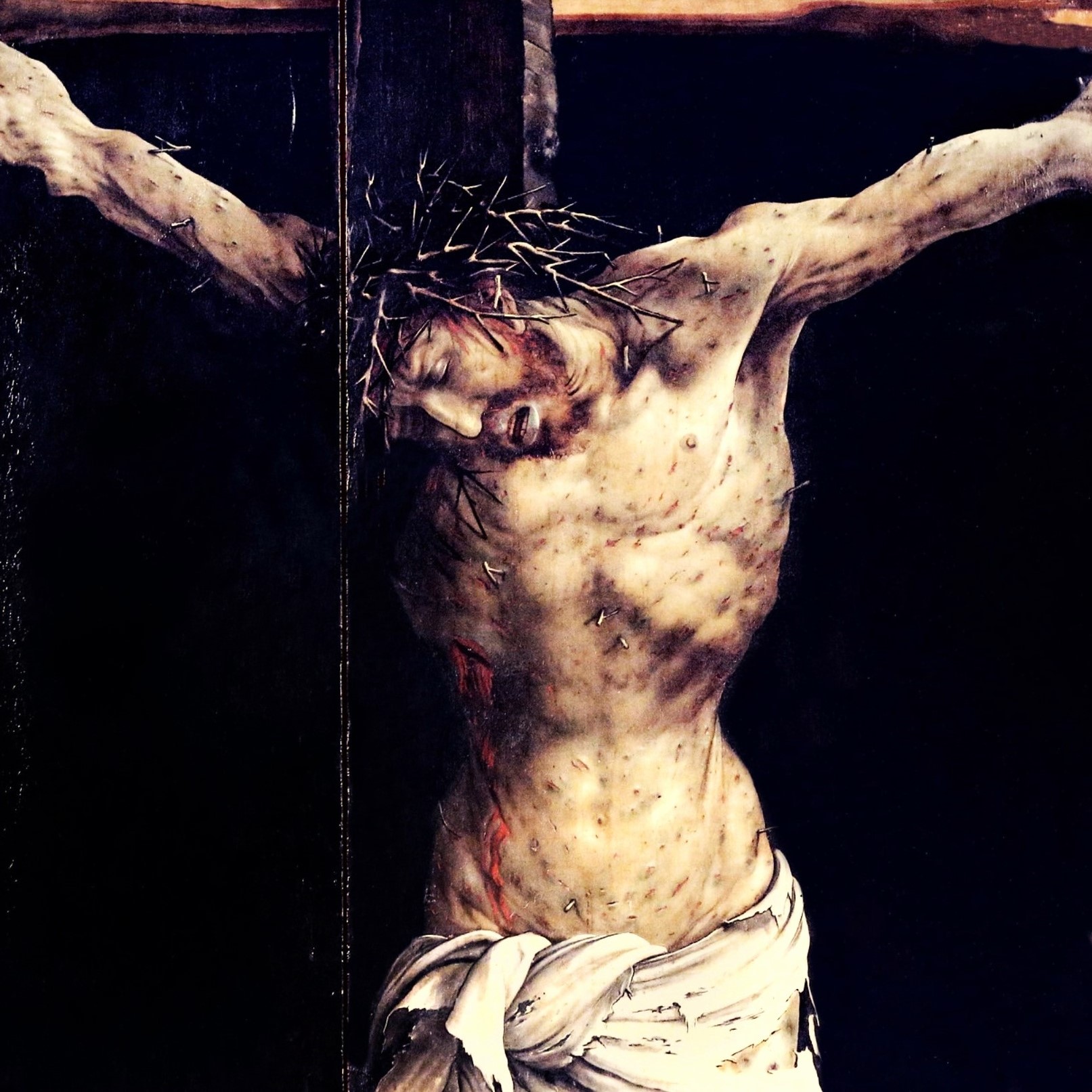

For Our Sins

There is nothing particularly necessary about the maltreatment that Jesus suffers as part of His Passion. None of the animal sacrificial victims of the Old Law were abused prior to their sacrifice, and their slaughter was as humane as a sacrifice could be. Even the goat of Yom Kippur, upon which the sins of the Nation were placed, was simply let free. The abuse that Christ suffered prior to His death is a result of human choice, of human acrimony, having to be done because Christ chose to subject Himself to whatever man wished to do to Him. It is a reflection and manifestation of the malice that lies in the heart of man, the movement of pride and will to lash out against God. Jesus simply takes it and bears it all. Not just because He is atoning for past sins, but for these very present sins, and all future sins. For everything that man’s evil heart would like to do to his Creator, He simply takes it and offers forgiveness for every single lash of mistreatment and barb of abuse that we willingly do to Him. Because His mercy is greater than our wickedness and His love deeper than any dark place that we would seek to hide from His Face in shame.

Behold, But a Man

Pontius Pilate is altogether human, perhaps too human. He is a man of some knowledge, but not a man of conviction or ideals. Pilate knows that truth and justice are important but, likely due to being assigned to the provincial backwater of Roman Judaea, decidedly not Roman and filled with a plethora of competing political and religious worldviews, took a subjective stance on the issue. What mattered at the end of the day was not truth, but who wielded power. This was truth that could be known; because it was tangible; because it provided security and purpose.

The tussle of wills between himself and the Jews came down not to the truth of justice, but to the truth of who held power. Pilate holds power as the representation of Caesar – his rule is Caesar’s rule. Yet, he cannot simply order the Jews to follow the will of Caesar for the Sanhedrin have been permitted to control much, but not all, of daily religious life – and all of life for a Jew is religious – in Judea as a semi-independent authority and court of law. It is a tenuous relationship between antagonistic parties and one that comes to a head with the trial of Jesus.

The Sanhedrin has decided that Jesus must die for blasphemy for claiming to be the Son of God, yet a Roman governor would have no problem with such a claim, for Roman mythology is rife with gods in human form and sons and daughters of the gods. Thus, the pivot to the accusation that Jesus is a King, a figure, who by this very claim, sets himself at odds with the rule of Pilate and, ultimately, Caesar. Pilate doesn’t buy this nor the sense of impending peril that the Sanhedrin claim will come to pass should Jesus be allowed to live. He shows some wisdom.

Pilate doesn’t want to deal with the troubles of managing the Sanhedrin’s demands and seeks to find multiple ways around having to deal with them – for if they can leverage him to do their will, then his power, Caesar’s power, is diminished. This is sensed by the Chief Priests and the Jews of the crowd, for their argument for the death of Jesus shifts subtly: Should you not crucify this ‘troublemaker’, we will do everything that we are saying he would do. We have no king but Caesar, if you do our will. We will keep peace. We will pretend that you rule us if you but do our will and crucify this Jesus.

One of the fears of the Jewish leaders was that Jesus would be a political messiah, lead a revolt, and Rome would bring the weight of her legions down upon the peoples and grind them and the Holy City into dust (a fear which would come to pass a short few decades later during the First Jewish War when Titus marched on the city.) The it is better that one man should die than a people becomes Pilate’s rationale: better Jesus than him having to put down a rebellion caused by his refusal to crucify Jesus. Better to save their skin. Better to save his own skin. Perhaps the Jews were bluffing, and they wouldn’t actually revolt. Their leaders did not want the Roman legions to descend upon them; after all, that was one of the points of having Jesus executed. Pilate folds.

Despite the implied impending possibility of carnage, Pilate’s signing of Jesus’ execution order may not be considered an act of wisdom or prudence. It is a travesty of justice and a bending to mob rule. Pilate may have washed his hands, but he is not free from the blood guilt of having, through the color of law, condemned Jesus, who was innocent of the charges according to Roman law, to death. We also live in a world of pragmatic cowards who seek not to do the things that are true, beautiful, or good, let alone that which is simply “the law”, but who seek ways out of doing what is hard, of what is heroic. They seek Pilate’s way to maintain balance, to ensure the prolongation of the status quo. It is a false vision that looks to misguided earthly considerations, not willing to do the right thing when it is hard, when it is inconvenient, when there is possibility for costs.

Seeking truth, knowing truth, and following truth have consequences. Truth casts light into darkness and darkness revolts against such intrusion for light and dark cannot coexist. But turning aside from the truth, seeking to coexist with the darkness has far more deadly consequences; while there is light, hope remains for those that live in darkness, but when one willingly steps into the darkness, one leaves behind hope. The darkness eats at the soul; compromise begets more compromise until all is consumed and nothing of the truth remains.

Pilate leaves his encounter with Jesus a broken and hollowed man, seemingly wandering off stage left diminished and in confusion.

And the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it.

Depictions of the Crucifiction of Christ typically end in darkness and silence. The heavens grow dark, the distant Father is seemingly silent in the face of the murder of His Only Begotten Son, life fades from the Incarnate Body of the Son, He is taken down, He is laid in a grave not His own. There is weeping, of no small amount, and people return to their homes.

This depiction is a sort of mental balm of the type that seeks to safeguard the human mind when it reels in anguish from a shock of incomprehensible horror and wonder. Christ sacrificed Himself for our sin, to restore broken man to God. This break happened because man attempted to kill God, drive Him from creation, from relationship with him, from his heart. The deicide of God committed by man is not just at Cavalry but began in the Garden and has happened every day since. There is a cosmic horror in God permitting man to attempt to kill Him, seemingly doing so, but then showing that such an attempt by man is only caught up as an instrument into things more wonderful than can be imagined to become the very means by which God reconciles humanity to Himself and to go beyond that by showing forth a new creation; the way of grace by which man should be united with God and share in His very own life.

This is altogether too much for the mind of man, which cannot comprehend such a bright light. The mind makes a mental block and Good Friday becomes a time of abandonment and darkness. This is but a fiction. Good Friday in reality was a day of upheaval, of endings of old ways, of theophany, and revelation. It is the silent voice of the Father speaking, clear to those who can hear it, clear to those who fall down in worship of the Crucified Savior.

— PPP