Translation of the Holy Gospel According to Matthew (4:1-11)

At that time Jesus was led by the spirit into the desert, to be tempted by the devil. And when he had fasted forty days and forty nights, afterwards he was hungry. And the tempter coming said to him: ‘If thou be the Son of God, command that these stones be made bread.’ Who answered and said: ‘It is written, Not in bread alone doth man live, but in every word that proceedeth from the mouth of God.’

Then the devil took him up into the holy city, and set him upon the pinnacle of the temple, And said to him: ‘If thou be the Son of God, cast thyself down, for it is written: That he hath given his angels charge over thee, and in their hands shall they bear thee up, lest perhaps thou dash thy foot against a stone.’ Jesus said to him: ‘It is written again: Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God.’

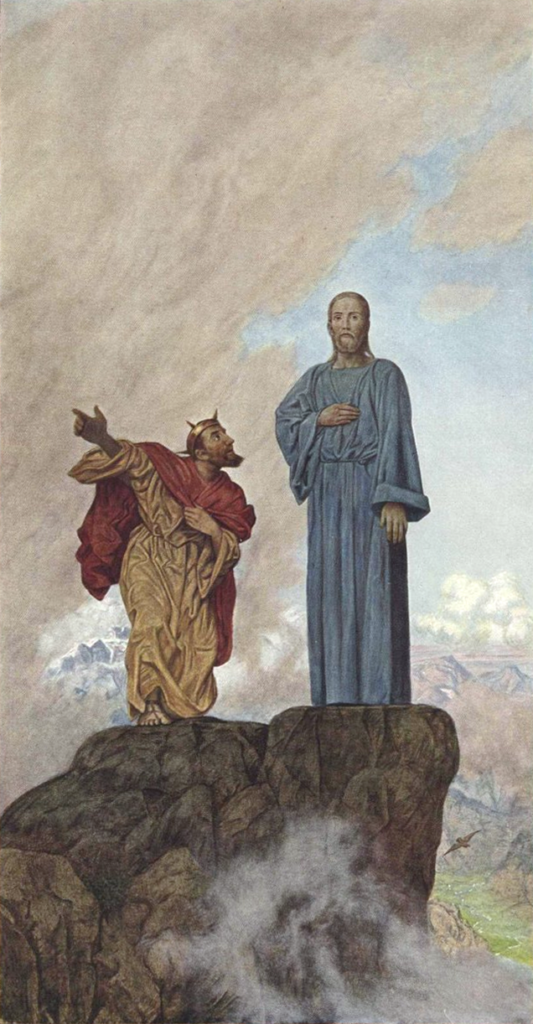

Again the devil took him up into a very high mountain, and shewed him all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them, And said to him: ‘All these will I give thee, if falling down thou wilt adore me.’ Then Jesus saith to him: ‘Begone, Satan: for it is written, The Lord thy God shalt thou adore, and him only shalt thou serve.’ Then the devil left him; and behold angels came and ministered to him.

A Message from St. Pope John Paul II’s Address to the Third General Conference of the Latin American Episcopate, 1979.

It is from a solid Christology that there must come light on so many doctrinal and pastoral themes and questions…

And then we have to confess Christ before history and the world with a conviction that is profound, deeply felt and lived, just as Peter confessed him: You are the Christ the Son of the living God (Matt 16:16).

…

This is the one Gospel, and even if we, or an angel from heaven, should preach to you a gospel contrary to that which we preached to you, let him be accursed, as the Apostle wrote in very clear terms (Gal 1:8).

In fact, today there occur in many places—the phenomenon is not a new one—”re-readings” of the Gospel, the result of theoretical speculations rather than authentic meditation on the word of God and a true commitment to the Gospel.

They cause confusion by diverging from the central criteria of the faith of the Church, and some people have the temerity to pass them on, under the guise of catechesis, to the Christian communities.

In some cases either Christ’s divinity is passed over in silence, or some people in fact fall into forms of interpretation at variance with the Church’s faith. Christ is said to be merely a “prophet”, one who proclaimed God’s Kingdom and love, but not the true Son of God, and therefore not the centre and object of the very Gospel message.

In other cases people claim to show Jesus as politically committed, as one who fought against Roman oppression and the authorities, and also as one involved in the class struggle. This idea of Christ as a political figure, a revolutionary, as the subversive man from Nazareth, does not tally with the Church’s catechesis. By confusing the insidious pretexts of Jesus’ accusers with the—very different—attitude of Jesus himself, some people adduce as the cause of his death the outcome of a political conflict, and nothing is said of the Lord’s will to deliver himself and of his consciousness of his redemptive mission. The Gospels clearly show that for Jesus anything that would alter his mission as the Servant of Yahweh was a temptation (cf. Matt 4:8 Luke 4:5). He does not accept the position of those who mixed the things of God with merely political attitudes (cf. Matt 22,21; Mark 12:17; John 18:36). He unequivocally rejects recourse to violence. He opens his message of conversion to everybody, without excluding the very Publicans. The perspective of his mission is much deeper. It consists in complete salvation through a transforming, peacemaking, pardoning and reconciling love. There is no doubt, moreover, that all this is very demanding for the attitude of the Christian who wishes truly to serve his least brethren, the poor, the needy, the emarginated; in a word, all those who in their lives reflect the sorrowing face of the Lord (cf. Lumen Gentium 8).

Against such “re-readings” therefore, and against the perhaps brilliant but fragile and inconsistent hypotheses flowing from them, Evangelization in the present and future of Latin America cannot cease to affirm the Church’s faith: Jesus Christ, the Word and the Son of God, becomes man in order to come close to man and to offer him, through the power of his mystery, salvation, the great gift of God (cf. Evangelii Nuntiandi 19 and 27).

This is the faith that has permeated your history and has formed the best of the values of your peoples and must go on animating, with every energy, the dynamism of their future. This is the faith that reveals the vocation to harmony and unity that must drive away the dangers of war in this continent of hope, in which the Church has been such a powerful factor of integration. This is the faith, finally, which the faithful people of Latin America through their religious practices and popular piety express with such vitality and in such varied ways.

From this faith in Christ, from the bosom of the Church, we are able to serve men and women, our peoples, and to penetrate their culture with the Gospel, to transform hearts, and to make systems and structures more human.

Any form of silence, disregard, mutilation or inadequate emphasis of the whole of the Mystery of Jesus Christ that diverges from the Church’s faith cannot be the valid content of evangelization. Today, under the pretext of a piety that is false, under the deceptive appearance of a preaching of the Gospel, some people are trying to deny the Lord Jesus, wrote a great Bishop in the midst of the hard crises of the fourth century. And he added: I speak the truth, so that the cause of the confusion that we are suffering may be known to all. I cannot keep silent (Saint Hilary of Poitiers, Contra Auxentium, 1-4). Nor can you, the bishops of today, keep silent when this confusion occurs.

This is what Pope Paul VI recommended in his opening discourse at the Medellin Conference: Talk, speak out, preach, write. United in purpose and in programme, defend and explain the truths of the faith by taking a position on the present validity of the Gospel, on questions dealing with the life of the faithful and the defence of Christian conduct … (Pope Paul VI’s, Address to the Bishops of Latin America at the Medellin Conference, 24 August 1968).

…

The Church is born of our response in faith to Christ. In fact, it is by sincere acceptance of the Good News that we believers gather together in Jesus’ name in order to seek together the Kingdom, build it up and live it (cf. Evangelii Nuntiandi 13). The Church is the assembly of those who in faith look to Jesus as the cause of salvation and the source of unity and peace (Lumen Gentium 9).

But on the other hand we are born of the Church. She communicates to us the riches of life and grace entrusted to her. She generates us by baptism, feeds us with the sacraments and the word of God, prepares us for mission, leads us to God’s plan, the reason for our existence as Christians. We are her children. With just pride we call her our Mother, repeating a title coming down from the centuries, from the earliest times (cf. Henri de Lubac, Méditation sur l’Eglise).

She must therefore be called upon, respected and served, for one cannot have God for his Father, if he does not have the Church for his Mother (Saint Cyprian, De Unitate Ecclesiae, 6, 8), one cannot love Christ without loving the Church which Christ loves (cf. Evangelii Nuntiandi 16), and to the extent that one loves the Church of Christ, he possesses the Holy Spirit (Saint Augustine, In Ioannem tract., XXXII, 8).

Love for the Church must be composed of fidelity and trust…

…

There is no guarantee of serious and vigorous evangelizing activity without a well-founded ecclesiology.

The first reason is that evangelization is the essential mission, the distinctive vocation and the deepest identity of the Church, which has in turn been evangelized (Evangelii Nuntiandi 14-15; Lumen Gentium, 5). She has been sent by the Lord and in her turn sends evangelizers to preach not their own selves or their personal ideas, but a Gospel of which neither she nor they are the absolute masters and owners, to dispose of it as they wish (Evangelii Nuntiandi 15). A second reason is that “evangelization is for no one an individual and isolated act; it is one that is deeply ecclesial (ibid. 60), which is not subject to the discretionary power of individualistic criteria and perspectives but to that of communion with the Church and her pastors (cf. ibid.).

…

In the abundant documentation with which you have prepared this Conference, especially in the contributions of many Churches, a certain uneasiness is at times noticed with regard to the very interpretation of the nature and mission of the Church. Allusion is made, for instance, to the separation that some set up between the Church and the Kingdom of God. The Kingdom of God is emptied of its full content and is understood in a rather secularist sense: it is interpreted as being reached not by faith and membership in the Church but by the mere changing of structures and social and political involvement, and as being present wherever there is a certain type of involvement and activity for justice. This is to forget that the Church receives the mission to proclaim and to establish among all peoples the Kingdom of Christ and of God. She becomes on earth the seed and beginning of that Kingdom (Lumen Gentium 5).

In one of his beautiful catechetical instructions Pope John Paul I, speaking of the virtue of hope, warned that it is wrong to state that political, economic and social liberation coincides with salvation in Jesus Christ, that the Regnum Dei is identified with the Regnum hominis.

In some cases an attitude of mistrust is produced with regard to the “institutional” or “official” Church, which is considered as alienating, as opposed to another Church of the people, one “springing from the people” and taking concrete form in the poor….

The truth that we owe to man is, first and foremost, a truth about man. As witnesses of Jesus Christ we are heralds, spokesmen and servants of this truth. We cannot reduce it to the principles of a system of philosophy or to pure political activity. We cannot forget it or betray it.

Perhaps one of the most obvious weaknesses of present-day civilization lies in an inadequate view of man. Without doubt, our age is the one in which man has been most written and spoken of, the age of the forms of humanism and the age of anthropocentrism. Nevertheless it is paradoxically also the age of man’s deepest anxiety about his identity and his destiny, the age of man’s abasement to previously unsuspected levels, the age of human values trampled on as never before.

How is this paradox explained? We can say that it is the inexorable paradox of atheistic humanism. It is the drama of man being deprived of an essential dimension of his being, namely, his search for the infinite, and thus faced with having his being reduced in the worst way. The Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et Spes plumbs the depths of the problem when it says: Only in the mystery of the Incarnate Word does the mystery of man take on light (Gaudium et Spes 22).

Thanks to the Gospel, the Church has the truth about man. This truth is found in an anthropology that the Church never ceases to fathom more thoroughly and to communicate to others. The primordial affirmation of this anthropology is that man is God’s image and cannot be reduced to a mere portion of nature or a nameless element in the human city (cf. ibid. and 14). This is the meaning of what Saint Irenaeus wrote: Man’s glory is God, but the recipient of God’s every action, of his wisdom and of his power is man (Saint Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses, III, 20, 2-3).

…

Faced with so many other forms of humanism that are often shut in by a strictly economic, biological or psychological view of man, the Church has the right and the duty to proclaim the Truth about man that she received from her teacher, Jesus Christ. God grant that no external compulsion may prevent her from doing so. God grant, above all, that she may not cease to do so through fear of doubt, through having let herself be contaminated by other forms of humanism, or through lack of confidence in her original message.