Translation of the Epistle for Passion Sunday

Brethren: When Christ appeared as high priest of the good things to come, He entered once for all through the greater and more perfect tabernacle, not made by hands – that is, not of this creation, – nor again by virtue of blood of goats and calves, but by virtue of His own blood, into the Holies, having obtained eternal redemption. For if the blood of goats and bulls and the sprinkled ashes of a heifer sanctify the unclean unto the cleansing of the flesh, how much more will the Blood of Christ, Who through the Holy Spirit offered Himself unblemished unto God, cleanse your conscience from dead works to serve the living God? And this is why He is mediator of a new covenant, that whereas a death has taken place for redemption from the transgressions committed under the former covenant, they who have been called may receive eternal inheritance according to the promise, in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Continuation of the Holy Gospel According to Saint John

At that time, Jesus said to the crowds of the Jews: Which of you can convict Me of sin? If I speak the truth, why do you not believe Me? He who is of God hears the words of God. The reason why you do not hear is that you are not of God. The Jews therefore in answer said to Him, Are we not right in saying that You are a Samaritan, and have a devil? Jesus answered, I have not a devil, but I honour My Father, and you dishonour Me. Yet, I do not seek My own glory; there is One Who seeks and Who judges. Amen, amen, I say to you, if anyone keep My word, he will never see death. The Jews therefore said, Now we know that You have a devil. Abraham is dead, and the prophets, and You say, ‘If anyone keep My word he will never taste death.’ Are You greater than our father Abraham, who is dead? And the prophets are dead. Whom do You make Yourself? Jesus answered, If I glorify Myself, My glory is nothing. It is My Father Who glorifies Me, of Whom you say that He is your God. And you do not know Him, but I know Him. And if I say that I do not know Him, I shall be like you, a liar. But I know Him, and I keep His word. Abraham your father rejoiced that he was to see My day. He saw it and was glad. The Jews therefore said to Him, You are not yet fifty years old, and have You seen Abraham? Jesus said to them, Amen, amen, I say to you, before Abraham came to be, I am. They therefore took up stones to cast at Him; but Jesus hid Himself, and went out from the temple.

The Saving Words of the Gospel.

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, the Holy Ghost. Amen.

Jesus hid himself.

Lent has several stages. There’s a particular itinerary that He follows, and we see it in the Gospels, and we follow a somewhat different itinerary. The itinerary of Christ in First Sunday of Advent, He was on the defensive when He was attacked by Satan and sends him packing. And then, we see this other encounter in which Our Lord speaks of Himself as the stronger man who binds the strong man and takes what he has plundered, which is basically our souls. So, Christ who is the stronger man binds the strong man Satan and strips from him the booty that he has stolen; the loot that is our souls. So, this refers to the Harrowing of Hell on Holy Saturday. It also refers to every confession, every baptism where Our Lord takes to Himself what belonged to Satan. And then, finally, we have on Palm Sunday Christ as king, and priest, and victor. That’s so much for His itinerary in Lent, ours is a bit different.

We have the Three weeks of Septuagesima in which we are preparing – we prepared for Lent. And then, we have the first four weeks of Lent, which are a time of reparation. These last two weeks are more a time of mourning and grief.

And so, now we are invited to enter into the mystery with Christ, the mystery of the Divine Bridegroom who suffers mockery, sorrow, grief, and passion, and lovers suffer with their beloved. And so, this is the time to enter into His pain. And so, in this spirit of grief, we have the statues covered. In the spirit of grief, we don’t say the Gloria Patri prayer during the Mass. The priest did not say Psalm 42 at the foot of the altar. So, [the Mass] takes on kind of a shape of a funeral Mass.

This hiddenness of the statues is tied to Christ hiding Himself in the Temple. The medieval French bishop Durandus connects the veiling of the statues with the hiddenness of Christ in this Gospel. Saint Gregory the Great and Saint Thomas Aquinas both agree that Christ made Himself invisible in order to walk through the crowd so as to avoid being stoned by them. Why? Because that is not how He wanted to die. He wanted to die on the Cross. And so, He avoided the easy way out by being stoned, by becoming invisible and walking through the crowd. And this invisibility of Christ then, in a certain sense, is extended to the saints as the statues are veiled.

There was a German medieval practice of what’s called the Hungertuch, and the Hungertuch was a linen veil that would cover the entire sanctuary. So, except for Sundays, every Mass was veiled. And all you could do is hear the bell of the of the server, perhaps their mumbled responses at the foot of the altar. But the entire mystery was hidden from the faithful. And there are still some of these Hungertüchen in existence. You can find them in some cathedrals and museums throughout Germany, and Austria, and other German-speaking countries.

This hiddenness of Christ is by His own choice, and it points to, above all, the hiddenness of His Divinity in the Passion. That’s where His Divinity is most veiled.

But there’s also a culpable hiddenness when we are not faithful to our consciences when we do not obey the will of God, then we, in a certain sense, hide Him from ourselves, or we hide ourselves from Him. There is a break in communication. We really have to get in the habit of not seeing sin as breaking a rule, but sin breaks His Heart. Sin breaks a relationship. Sin breaks ourselves. And even though we go to Confession, there is still brokenness that is residual from that wound that we’ve inflicted upon ourselves. And it’s in the order of an attachment to sin, and this very attachment to sin, even though I’ve been forgiven of my sin, this remains.

This perduring attachment to sin is another type of a hiddenness in which I choose something as a greater good than the Blessed Trinity. What could that be? Well, take your pick. Every one of us has chosen a greater good than the Blessed Trinity in every sinful choice. That’s the definition of a sin to say this is better for me than you. We perhaps don’t say it at the moment of temptation, but in effect, that is the fruit of the choice.

St. Augustine says in his Confessions:

You were within me, but I was outside of myself and sought you there. And in my unlovely state, I plunged into those lovely, created things that you made. You were with me, and I was not with you. The lovely things kept me from you, though if they had not had their existence in you, they would have had no existence at all. You called and cried aloud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent. You put the flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew in my breath, and now I pant after you. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you. You touched me, and I was set on fire to attain the peace which is yours.

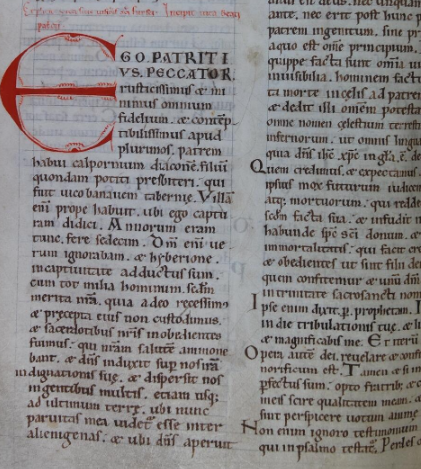

Similarly, there’s another great saint that we celebrate today who also wrote his own confession called the Confessio of St. Patrick. I recommend you look it up. It’s only 21 pages of PDF. You can find it online and read his autobiography of his conversion. It’s beautiful. He speaks in a very rudimentary way. The Latin, if you know Latin, read it. It’s simple Latin, but it’s not a very elegant Latin. He wasn’t that well educated, but it’s very beautiful to see how Patrick in his Confessio speaks of how God worked on his soul when he had hidden himself from God through sin.

He was a young, superficial man who came from a very devout family, but he chose to use his freedom in a different way. He grew up in Scotland and was kidnapped by Irish pirates and brought to Ireland as a slave. And there, part of his task was to tend sheep. So he would be out in the field with the sheep and thinking of home. Thinking of whatever occurred to him, and in the silence of his loneliness, he started to pray again. And this was the beginning of the workings of grace in his soul. And through his silent prayer, he became a man. And through his silent prayer, he became a man of God, and eventually St. Patrick, he says in his Confessio:

And there the Lord opened my mind to an awareness of my unbelief, in order that, even so late, I might remember my transgressions and turn with all my heart to the Lord my God, who had regard for my insignificance and pitied my youth and ignorance. And he watched over me before I knew him, and before I learned sense or even distinguished between good and evil, and he protected me, and consoled me as a father would his son.

So, Patrick’s silence went from an absence of sound to an encounter. You know, there are different types of silence. There’s the silence of, you know, eight people stuck between floors in an elevator. That’s kind of an uncomfortable silence. There’s also a silence that you find here on Friday nights during Adoration, which is a very full living silence, and that’s the silence of recollection. Something’s happening, something’s at work. Grace is working on our souls and we’re making acts of love to Our Lord.

We have another great saint this week, the saint of silence which is St. Joseph who never said a word in Scripture, and nonetheless, his silence was a silence of adoration, a silence of vigil, and this vigilance was, in the first place, over his own heart to keep it pure and alone for Our Lord. His silence was gratitude, his silence was recollection, his silence was adoration, was wonder at watching the Blessed Mother, wonder at watching the Christ child. His silence was vigilance as he protected and provided for the Holy Family.

Benedict XVI says:

St Joseph’s silence does not express an inner emptiness but, on the contrary, the fullness of the faith he bears in his heart, and which guides his every thought and action.

It is a silence in unison with Mary, as St. Joseph watches over the Word of God, known through the Sacred Scriptures, continuously comparing it with the events of the life of Jesus; a silence woven of constant prayer, a prayer of blessing of the Lord, of the adoration of his holy will and of unreserved entrustment to his providence.

Let us allow ourselves to be “filled” with St Joseph’s silence! In a world that is often too noisy, that encourages neither recollection nor listening to God’s voice, we are in such deep need of it.

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, the Holy Spirit. Amen.

— Fr. Ermatinger